Flux Quartet ready for full immersion in Feldman’s six-hour String Quartet No. 2

Morton Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2 will be performed by the Flux Quartet April 26 at the Park Avenue Armory.

What is it like to experience a six-hour piece of music? What is it like to play?

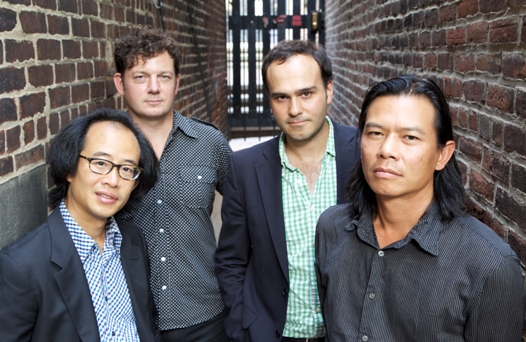

On April 26 at the Park Avenue Armory, the Flux Quartet will perform Morton Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2, a magnificent composition that has the remarkable duration of six hours. Flux is one of the foremost groups playing modern and contemporary music, and they have made something of a speciality of the piece, including a 2002 recording on Mode Records.

In the past twelve years, the group has played the piece a dozen times, through numerous changes in personnel. Violinist Tom Chiu is the only member left from the recording, and he is now joined by violinist Conrad Harris, violist Max Mandel and cellist Felix Fan.

The current Flux lineup has appreciable experience with the piece—this will be their third performance since last fall. (The quartet will finish their cycle of the complete Feldman quartets—the first on disc—for Mode with the release, on April 29, of a 2-CD set of the String Quartet No. 1 and the early Three Pieces and Structures. The recording will be available for pre-release purchase at the Armory concert.)

This will also be the second program of one of Feldman’s extreme-duration works since the Armory refurbished their Board of Officers room and began presenting chamber music series inside: Anton Bagatov performed Triadic Memories, a solo piano work that approaches two hours in length, last October.

Feldman is a major figure, one of the greatest post-World War II American composers, yet he is more frequently read about than performed.

The Flux Quartet members jumped at the chance to play the String Quartet No. 2 again, despite what seems like the impossible demands it places on musicians, and even audiences: up to six hours playing, and listening to, one uninterrupted piece of music, with only a few brief moments where there is silence.

Long concerts and performances, long musical experiences, are nothing new in classical music, but a single work dedicated to such long duration is still exceedingly rare, outside of Wagner operas.

Talk with the Flux musicians, though, and the challenges sound almost trivial. “It’s an emotionally and mentally transforming experience,” says Mandel. “When you’re in it, it’s so hardcore that you don’t think about your body.”

“I’ve never thought about [thirst and hunger],” Harris adds. There’s never been any urgency to make a bathroom trip as well, they say. They are playing, concentrating, active in every moment, all other needs fall away.

For the audience, though, this is different. The quartet doesn’t mind if people take a break to stretch or go to the bathroom. “Oh no, it’s not a problem,” Harris says. “Feldman expected it.” But their experience has been that most people stick with the music all the way through. “People get quieter and quieter, and more focused, and it becomes a special place,” says Fan.

Quiet is one of Feldman’s fundamental musical values. The score has many moments of forte and mezzoforte, but the predominant level is pianissimo, and there are more than a few markings of quintuple piano. To Chiu, the dynamic range rivets the audience: “Volume is relative. After you set in at that level, your ears adjust, and you’re in another world.”

“[Feldman] is one of those important composers who advanced the art form, and invented musical languages that have become hugely influential,” says Alex Poots, the Armory’s artistic director. Poots, a UK native and a composer by training, believes there is a huge center of gravity in 20th-century American music and that Feldman is “a bridge to the modern sound” of minimalism and post-minimalism.

Even in Feldman’s substantial body of work, these pieces are unusual and require dedicated musicians. Poots makes programs by “trying to find the best group of musicians, and [then] it’s entirely their choice. [Triadic Memories] was [Bagatov’s] idea, same with the quartet.

“I’m very keen on single composer recitals, so when you find someone who is particularly good for a recital, my only request is ‘you do an all so-and-so recital.‘ They jumped at it.”

In the Board of Officers room, the quartet will sit in the center, surrounded by the audience. The acoustics of the room are exceptional and proved ideal for Triadic Memories. Once the doors are closed, outside noise is effectively muffled, and the resonance is full and clear, completely without distortion, at every dynamic level. The sheer beauty of the sound should ease the mental effort needed to listen.

The repertory of music with long duration is infinitesimal, even esoteric. Satie’s Vexations has a related form in that it uses extended repetitions of small bits of material, but the goal is continuation, duration. The English eccentric Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji wrote music of frequently punishing duration, such as the four-hour Opus Clavicembalisticum for solo pianist, but his music is high-romanticism blown up to gargantuan proportions. The running time for a performance of Götterdämerung can approach six hours, but that is an epic narrative, moving forward via separate scenes with extended intermission breaks.

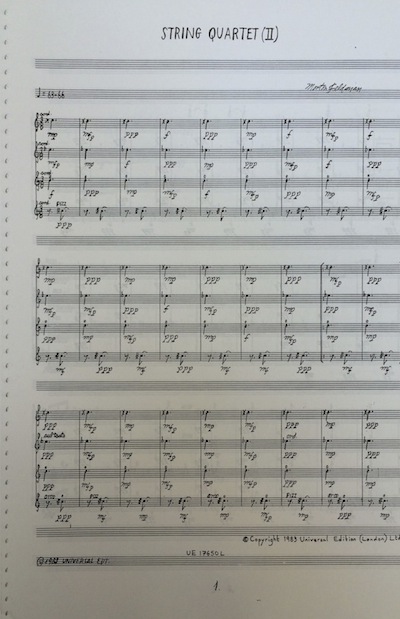

Feldman’s ideas share nothing with the above but time, and his notion of that dimension is entirely different. When he composed long works like String Quartet No. 2 and For Philip Guston, he had left behind his early experiments with graphic notation, open forms and improvisation, and gone through a middle period where he experimented with combining unsynchronized instrumental lines in such pieces as Why Patterns? By the mid–1980s, Feldman was using plain, standard musical notation, every note, rest and dynamic marking written out.

The result is a piece of music that happens to take between five and one-half and six hours to play (the Mode recording is precisely six hours, seven minutes and seven seconds, and Flux finds they’ve currently hit a consistent “sweet spot” at five hours and forty minutes).

The music is not made in order to last for a long time, instead the music is made to go from the first bar to the last, and takes a long time to complete. That distinction is crucial: the String Quartet No. 2 is not an experimental or aleatoric work—designed to see what might happen—nor is it a particularly avant-garde piece, made in order to provoke some element of the Western classical tradition.

Beginning with a tempo marking of quarter note equal to 63–66 beats per minute, and a series of tone-clusters, the piece slowly builds a quasi-traditional large scale structure through the simplest and subtlest means.

Feldman wanted his music to be slow and quiet, but he did not want it to be boring or mindlessly repetitive. String Quartet No. 2 has an easily identifiable introductory section, a few important interludes and even a pause, with true silence, leading to a coda. The bulk of the work is made up of single bar phrases—rapid little runs and, especially, an important phrase that sounds like it’s rocking back and forth, and through which we can hear clear harmonic motion—each repeated several times—even up to eleven. These phrases are almost literally musical bricks, each one laying out a bit of the work, the shape and experience which comes through in their accumulation.

In a sense, nothing could be more classical, although Feldman eschews the idea of development that dominated 19th-century music. Hearing the entire quartet as an enormously long sonata-allegro movement is not beyond the limits of reasonable argument. But the real form and point of the piece is time, and the how time can be static, and how musical structure and expression can do something, anything, other than move the piece along to an anticipated harmonic and/or dramatic resolution.

There are plenty of technical challenges: Feldman writes a phrase, then varies it with slight, but exact, changes in rhythm, and the musicians must play that clearly. The opening pages call for each instrument to play at a different dynamic, changing in almost every measure. There are extraordinarily complex rhythms, and clusters of harmonics that are a challenge to keep in tune.

“We didn’t meet Feldman in his lifetime, but we think he’s a really funny guy,” said Chiu with a laugh, “When you look through this piece, there’s so many ways he [screws] with his musicians. I mean, look at these notes!”

Counting is difficult, not just maintaining the tempo (the group usually follows an eighth-note pulse), but in keeping the exact number of repetitions in order. Everyone has to be constantly alert.

Mandel says, “if my brain is fried after four hours … [and] you have a repetition that’s eleven times, I have my count. But we’ve appointed Tom as the boss of when we go on, so if my count is different from Tom’s I have to be able to let go of it and immediately jump, even if I think he’s only done it ten times … so the focus is so local” and unwavering. Harris agrees: “Mental preparation, that’s the most challenging for me.”

They do look for moments for the briefest mental breath. “There are places where we take an orchestrated break” explains Chiu, at points where there is a rest or a brief pause. “If it makes musical sense” Mandel adds, “we do it mainly for pagination.”

Those pages: 124 of them, hours and hours of notes, with nary a crescendo or a dense moment. There are too many pages and too many hours to actually rehearse the entire piece. Instead, the quartet works on sections that each member chooses, solving problems of coordination, maintaining tempo when the rhythms change drastically, keeping the dynamics right. The pages are the point: “Why do we want to commit five and half, six hours to sitting here, obeying the score?” Chiu asks. “It’s because it’s just such a great piece of music. Every page could be its own piece.

“There are pages that are very frustrating for us, but those make the other pages that much more worthwhile,” says Chiu. “It’s one of those rare pieces that’s almost like the Bible—you revere it. And the commitment you make to play it means that ultimately all the challenges and difficulties fall by the wayside.”

The Flux Quartet will perform Morton Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2 at 3 p.m. April 26 at the Park Avenue Armory. armoryonpark.org.