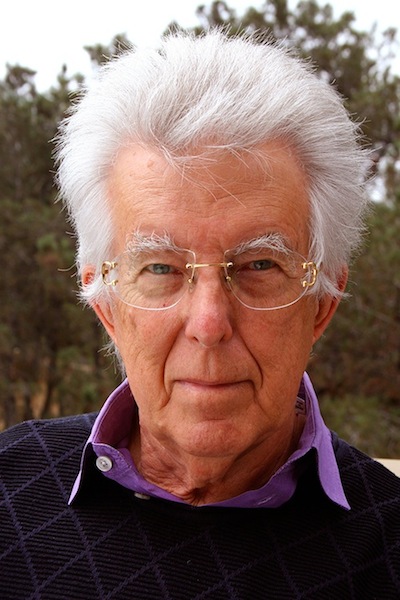

Mesmerizing and beguiling, Roger Reynolds’s music receives its due at Miller Theatre

Hearing the sounds is what makes things happen,” said Roger Reynolds during the on-stage discussion at his Composer Portrait concert Saturday night at Miller Theatre.

That simple phrase gets to the core of Reynold’s music. His career has been shaped by epiphanies and happy accidents: hearing a Horowitz record as a boy, taking a composition for non-majors class with Ross Lee Finney at University of Michigan, hearing the digital music being explored at Stanford University. Reynolds kept discovering just what he needed to find his way forward.

Hearing his mature music offers the same experience: there are sounds for the ear to discover, and further there is a pattern to these sounds that insinuates itself into the listener’s consciousness, leading to moments where an intriguing but opaque collection of musical events crystallizes into form and meaning.

The concert was also a showcase for the calm, implacable virtuosity of Reynolds’ longime friend and collaborator Irvine Arditti. Two of the three pieces on the program had the violinist at the forefront: the opening solo piece Kokoro, from 1993, and the closing work, Aspiration, a chamber-size violin concerto less than ten years old. For the latter, Arditti was backed by Ensemble Signal, conducted by Brad Lubman. A smaller cohort of Signal played the intervening work, 2012’s Positings, in its New York premiere.

Reynold’s music doesn’t sound as experimental as it is; he’s a classicist who explores the possibilities of notation, computer music, and electronically processed audio. His aesthetic world is the one Debussy founded, its virtues are clarity: a proportional—rather than linear—sense of time, and pleasure in pure sound. He frequently uses pure tones and their overtones—shimmering piano strings, chiming percussion, vibrato-less long tones on the violin—and these easy on the ear.

These qualities make even his most rigorous work accessible. What he creates may be utterly unfamiliar, but there is always sufficient space in time for musical events to resonate and sink in for the listener.

Kokoro is a cogent example of Reynolds’ balance between strict compositional architecture and an almost mystical sense of expression. He’s something of an ascetic of abstraction, with an implied search for otherworldly vision through limitations.

In Kokoro, written expressly for Arditti out of a collaboration between Reynolds and the Arditti Quartet, the music opens with a simple, conventional four-note phrase. Reynolds starts turning the music around, stretching and compressing it, moving it through the violin’s range, all standard techniques.

Positings has a similar formal structure, and adds another important feature of his thinking, the placement of sounds in space.

The instrumentation is for flute and piccolo, french horn, violin, cello and piano (the pianist also strikes gongs and triangles). There’s also a computer musician (Paul Hembreee, one of Reynold’s doctoral students), who samples the ensemble and plays back the snipped and processed sounds through a four-channel speaker system surrounding the theater. The quintet plays their music (mostly sustained tones, interspersed with rapid passages and some tutti climaxes) in a sequence, the computer plays back their playing in a different order, an antiphonal means turns into a complex temporal form in which future and past commingle.

The abstract simplicity of Positings seemed a challenge for both audience and musicians at first, the latter approached their attacks with a brittle, anxious feeling. But after the first computer response, both players and ears relaxed, and the piece became organic, logical and both sonically beautiful and emotionally beguiling in Reynolds’ distinctive way.

Compared to the first two pieces, Aspiration is almost conventional. This is a concerto where soloist and orchestra are, if not in opposition, then playing along parallel tracks that are related in the same way that an individual is related to the crown he happens to find himself in. Ensemble and soloist alternate playing—six ensemble passages and five solo cadenzas—then come together, at least in time, in the finale.

But a conventional concerto begins and then works its way to resolution: Aspirations rises slowly then falls, slowly. The orchestral passages seem to be built around respiration, mostly slow and relaxed and built around the duration of breath.

The cadenzas are entirely different: the first is rubato, the violin alternating close runs and wider leaps; the second repeats a firm, clear rhythmic pattern. The third combines the two, and adds lightning quick glissandos and harmonics. The part seems almost preposterously difficult (Reynolds apparently made it harder after Arditti mentioned that it wasn’t too challenging) and Arditti played it with remarkable precision and aplomb.

Easing down the back of the arch from this height, the solos return to sustained pitches and a freer rhythmic quality. In the finale, all the musicians exhale together in a moment of stillness.

Aspirations is Reynolds at his mesmerizing best. The ensemble serves to open up cracks in space and time that the violin fills with music that is intellectually exploratory and emotionally resonant.

Unsuk Chin is the subject of the next Composer Portrait, March 13, 8 p.m. millertheatre.org